Story Elements

Novels are complex things, made up of many elements, which are discussed here.

Setting

Setting, in a work of fiction, is the device used by the writer to establish three components that will be defining elements of your story:

- time

- location

- environment

These elements of the novel’s setting influence characters and events, and are essential to providing readers with the contexts they need to imagine those characters and events. Setting lets the reader in on the type of literary world he or she is entering.

SIDE NOTE: Novelist/educator John Gardner wrote the influential On Becoming A Novelist, in which he dispensed information good and bad (to my mind), but one particularly powerful concept he used was that of “the real toad in the imaginary garden”. You can imagine viewing a static scene in which something suddenly moves, drawing your eye to this living aspect within this static environment. Something has life.

Gardner used that concept of setting - the “imaginary garden” - and action - “the real toad” - to describe those moments in a two-dimensional narrative when suddenly a third, elevating dimension reveals itself. That’s when fiction comes to life.

Gardner borrowed the phrase from a poem by Marianne Moore (Poetry). In the poem, Moore says that poetry is about creating imaginary gardens with real toads in them, meaning that poetry should combine imagination and reality, and that it should present genuine things in a new and interesting way. That is a Bing robot summary of Moore’s thinking, which may or may not represent a full understanding of her thinking.

You need a setting appropriate for the active toad. If your toad is at all typical, it will probably be an outdoor setting, so already your toad story has parameters, a stage on which to act out the play.

A long work of fiction can have multiple settings, whether that means moving between different locations, different time periods, or different worlds. For example, in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, the setting shifts from the peaceful Shire to the dark Mordor, from the ancient Rivendell to the modern Minas Tirith, and from the Middle Earth to the Undying Lands. Each setting has its own characteristics, history, culture, and mood that affect the plot and the characters.

Setting can also be used to create contrast, suspense, foreshadowing, symbolism, and theme in a long work of fiction. For example, in Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, the setting alternates between London and Paris during the French Revolution. The two cities represent the contrast between order and chaos, stability and violence, loyalty and betrayal. The setting also foreshadows the fate of some characters who travel between the two cities. Moreover, the setting symbolizes the theme of resurrection and sacrifice that runs throughout the novel.

Therefore, setting is not just a backdrop for a story, but a vital element that shapes and enriches a long work of fiction.

Point of view

Point of view is a term that refers to the perspective from which a story is told. It determines who is narrating the story, how much they know, and how they relate to the reader. It shapes how the reader perceives and engages with the story. Point of view is an important choice for a writer, as it can affect the tone, mood, and meaning of the story.

THREE MAIN TYPES OF POINT OF VIEW

-

First Person: First person point of view uses the pronouns “I” and “we” to tell the story from the writer’s or a character’s point of view. The reader can access the narrator’s thoughts, feelings, and opinions directly, creating a sense of intimacy and connection. However, this point of view also limits the reader’s knowledge to what the narrator knows and experiences, which can be biased or unreliable. First person point of view is common in novels that are character-driven, such as young adult, science fiction, and memoir.

-

Second Person: Second person point of view uses the pronouns “you” and “your” to address the reader directly, as if they are part of the story. The reader becomes an active participant in the story, making choices and facing consequences. However, this point of view can also be intrusive or alienating, as it imposes a certain role and perspective on the reader.

Second person point of view is rare in novels, but it can be found in some experimental or interactive fiction. AUTHOR’S NOTE: I use second person POV from time-to-time in ATWOOD: A Toiler’s Weird Odyssey of Deliverance as a device to break down the wall that effective dramatic presentation is typically all about building. Many readers, not oriented to such audacity, find that jarring, but I chose to use the device (sparingly) to remind the reader that the novel, which seems a lot like historical fiction, is really a fantasy, a thing other than what it seems. It is about the development of the United States of America. You’d have to read the novel for any of that to make sense.

- Third Person: Third person point of view uses the pronouns “he”, “she”, “they”, and other names to tell the story from an outside or objective point of view. The reader can observe the actions and dialogues of multiple characters, as well as their thoughts and feelings if the narrator is omniscient (all-knowing). However, this point of view can also create a distance or detachment between the reader and the characters, as well as a loss of intimacy or voice. Third person point of view is common in novels that are plot-driven, such as fantasy, mystery, and historical fiction.

Third person point of view comes in two types: limited and omniscient:

-

In third person limited, the narrator only knows and reveals the thoughts and feelings of one character at a time.

-

In third person omniscient, the narrator knows and reveals everything about all the characters at any time.

Timeline

Time marches on - and it is good that it does, or your novel would never get off the starting blocks.

The timeline of a novel (and life) tracks the sequence of events, the character development, and the historical accuracy of the story.

Because we humans are quite familiar with the clock, and how it proceeds through every minute, every hour, every day, in a straight-forward fashion, developing a timeline for your novel comes pretty naturally. We think in linear terms, and that’s what a timeline is: a straight shot from the starting line to the final line. Timelines, in novel development, are both story drivers, and planning devices. You can use a graphic tool, a word document, or a spreadsheet.

-

Start by deciding the time span of your novel. How long does the story last? A day, a week, a year, a lifetime? This will help you determine the scale and scope of your timeline.

-

Identify the major events and milestones of your plot. These are the turning points, the climaxes, the conflicts, and the resolutions that move the story forward. Write them down in chronological order, along with the date and time they occur.

-

Fill in the gaps between the major events with smaller scenes and details. These are the actions and reactions that show how your characters react to the events, how they grow and change, and how they interact with each other. You can also add historical facts, background information, or foreshadowing clues that enrich your story.

-

Review your timeline and make sure it is consistent and coherent. Check for any errors, contradictions, or repetitions. Make sure your timeline matches your genre expectations and your target audience. Adjust or delete any scenes that are unnecessary or irrelevant to your plot.

Pace and Timelines

Developing a graphic timeline for your story is useful in helping the writer stay coordinated and consistent in the story-telling. Even more importantly, it is an aid to the reader, creating an order to events - logical or otherwise - giving them some bearing on how far they have progressed in their reading of the story, their immersion.

That is, of course, tricky for the writer. Events in the story must coordinate with the established timeline in ways that comport with the reader’s expectations given what they have read to at any one point. Writers orient their readers by dint of the pace developed for the timeline of a story. It is important that a writer remain consistent with the pacing of their story, their timeline. A story that rushes to a conclusion in some way not consistent with how the story has rolled out on the way to resolution - or is arrived at in a manner not consistent with what we know of the reality of passing time - will annoy a reader. They’ll feel the error in the writing, in the timeline, and they’ll resent that the story ended poorly, whatever happens in the final chapter. They’ll be responding to the handling of it all - of the writing itself, which is not really what the writer wants readers to be thinking about.

Timelines must feel natural, familiar. They are the anchor point we human readers have with fiction, the tether that ties imagination to something we know, think about constantly, and can’t avoid: time, and the passing of it. The writer must respect that and get the pacing of the timeline “right”.

Character Timelines

Because novels typically involved multiple characters, all of different ages, born at different times, maturing through different periods of history, a complex novel will, either actively or passively, be affected by, and possibly deal with, a number of timelines associated with each character.

Character timelines hugely impact character development. A ten year old behaves differently than does a twenty-five year old, because they are at different points in their timelines. Writers may make the choice to develop character back-stories, to explain their behaviors at some point in time.

Writers often use time shifting - flashbacks - to insert stories within the main story to add richness to overall narrative.

Obviously, this takes some careful planning and intuitive insight. If time-shifting flashback scenes are not handled sensitively, they may baffle and frustrate the reader.

Too much jumping aound a novel’s timeline, to tell character back=stories, can feel ham-handed. Here you have one of those differentiators, the type of handling issue that separates incompetent writers from the good, the professional, and the brilliant. AUTHORS NOTE: It seems to be “the professional” who gets the rare traditional publishing deal.

Voice

Voice, in writing a novel, refers to the perspective and tone of your narrator or your characters, and is as complex a topic as is any other aspect of novel writing. Voice is the way you express - through your words, sentences, and paragraphs - personality, opinion, and emotion.

A novel will have a voice - typically the voice of the narrator of the story, that gives the work an overall feel - but most novels involve a number of individual characters. Each of those characters, if you understand the character you are creating well (fully fleshed), you’ll “realize” their own natural voice. It is probably important that writers clearly hear their characters’ voices in his or her heads, at the very least - probably critical to creating truly engaging characters. Voices - the sound-feelings writers place in their readers’ minds - may make stories more engaging, unique, and authentic.

You, the writer, must make decisions asround how, and whether, to use those character voices in your story.

There are three voice types in writing a novel:

-

Author’s voice: This is the distinctive style and voice that makes your writing recognizable as yours. It is influenced by your word choice, syntax, punctuation, rhythm, and tone. It also reflects your worldview, values, and beliefs. Some authors who have a strong and recognizable voice are J.K. Rowling, Ernest Hemingway, and Jane Austen.

-

Character’s voice: This is the way your characters speak and think in your novel. It is influenced by their personality, background, age, gender, culture, and emotions. It also reveals their motivations, goals, and conflicts. Each character should have a unique and consistent voice that distinguishes them from others. Some characters who have a memorable and distinctive voice are Sherlock Holmes, Katniss Everdeen, and Holden Caulfield.

-

Narrator’s voice: This is the voice that tells the story in your novel. It is influenced by the point of view you choose for your novel, such as first person, third person limited, or third person omniscient. It also affects the mood, atmosphere, and suspense of your story. Some narrators who have a compelling and captivating voice are Nick Carraway from The Great Gatsby, Death from The Book Thief, and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

Attitude

Attitude in a novel is the way the author or the characters express their feelings, opinions, and perspectives about the subject matter of the story. Attitude can affect the tone, mood, and meaning of the novel, as well as the reader’s engagement and enjoyment of the story. Attitude can be conveyed through various elements of writing, such as word choice, sentence structure, figurative language, point of view, and details.

Some examples of attitude in novels are:

-

In The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger, the protagonist and narrator Holden Caulfield has a cynical, sarcastic, and rebellious attitude towards society and adulthood. He uses informal, colloquial, and slang language to express his thoughts and feelings, often criticizing or mocking the people and situations he encounters. His attitude reveals his alienation, confusion, and insecurity as a teenager who struggles to find his identity and purpose in life.

-

In Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen, the author has a witty, ironic, and satirical attitude towards the social norms and expectations of her time. She uses subtle humor, dialogue, and characterization to expose the flaws and follies of her characters, especially their prejudices and pride. Her attitude also reflects her feminist views and values, as she challenges the stereotypes and limitations imposed on women in her society.

-

In The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, the author has a critical, dystopian, and suspenseful attitude towards the futuristic world she creates. She uses vivid descriptions, action scenes, and symbolism to portray the harsh realities and injustices of a society where children are forced to fight to the death in a televised competition. Her attitude also evokes sympathy and admiration for her protagonist Katniss Everdeen, who defies the oppressive system and becomes a symbol of hope and resistance.

Plot

It may be useful, when thinking about the “plot” of your novel, to put yourself back in math class at school, when you used to “plot” points along the ‘X’ and ‘Y’ axes on graph paper.

Plot, in that example, is a verb, but it didn’t begin that way. How it become part of the lexicon is unclear. The word seems to exist only in the English language, and to have been invented as a noun in the 10th or 11th century to reference a small piece of land or area of ground (according to Dictionary.com).

If you imagine a birdseye view of a plot of land, you have a good starting point for imagining how plot, originally a noun, expanded to become the verb that it is today.

Just as you might place items or objects of interest on your plot of land - green grass, trees, flowers, a monument, a grave - and just as you might plot points on a graph, you will create plot points in the storyline of your novel that progress character development. That sense of the word “plot” seems to have entered into usage in the 16th Century, becoming a verb in hand with the parallel word “complot”, meaning “a secret plan for accomplishing a usually evil or unlawful end”. The 1605 “Gunpowder Plot” - a failed attempt by a group of Catholic conspirators to blow up the Houses of Parliament and kill King James I - cemented the use of the word “plot” as a verb. It describes a series of events leading to a resolution.

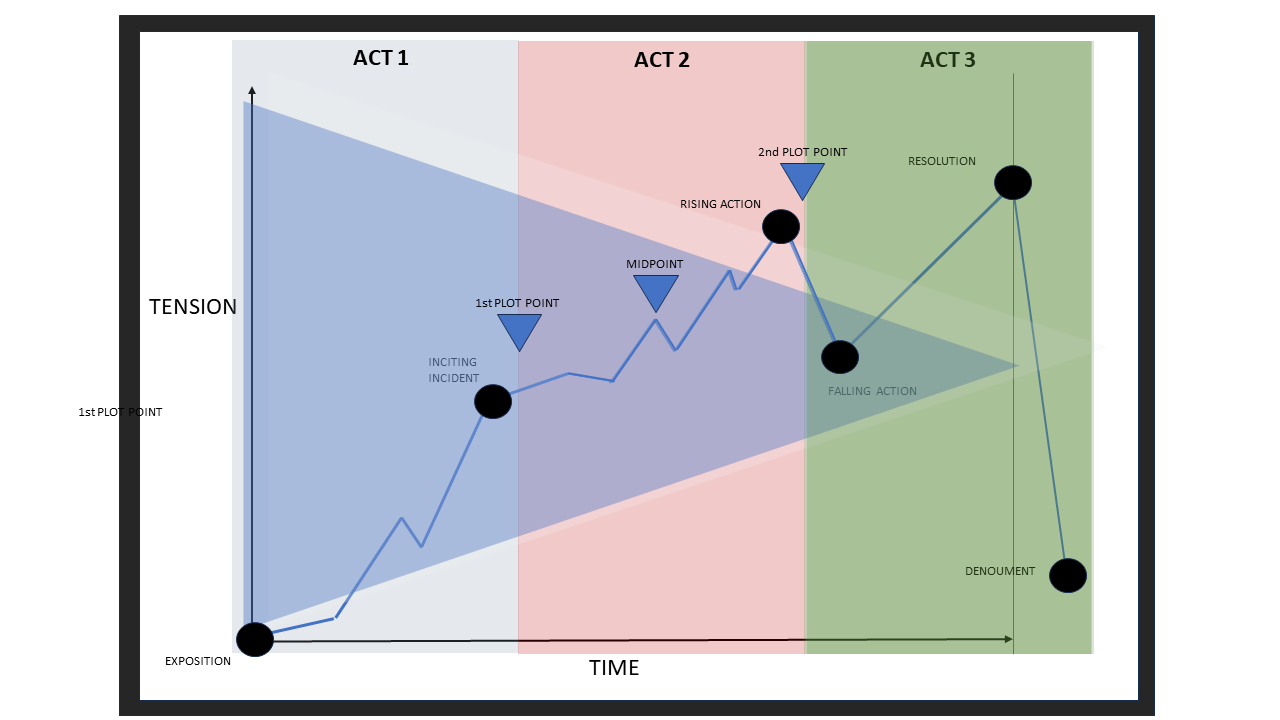

As discussed on the Outlining page of this site, the three-act format is a proven winner when it comes to formulating plot lines. It provides a useful way to unpack the basic elements of fiction. The ancient Greek dramatists are credited with developing a formula for story-telling that included the following plot elements (though apparently the word “plot” did not exist in their time):

- Exposition: the introduction of the setting, characters, and background information.

- Inciting Incident: the event that triggers the main conflict or problem.

- Rising Action or Progressive Complications: the series of events that increase the tension and stakes of the conflict.

- Dilemma: the point where the protagonist faces a difficult choice or a moral dilemma.

- Climax: the turning point or the most intense moment of the story.

- Denouement: the resolution or the outcome of the story.

German writer Gustav Freytag “codified” that formula in the middle of the 19th century. His take was built on the concepts attributed to Aristotle, who organized his plays in two main parts - the “complication” and the “denouement” - sandwiching around a “peripeteia” or a reversal of fortune.

Freytag’s take on the Greek tradition was called Freytag’s Pyramid. and it organized his elements of fiction in the three-act format:

-

Act One: Exposition introduces the setting, characters, and background information of the story.

- It presents the inciting incident*, which is the event that triggers the main conflict or problem of the story. The inciting incident marks the end of Act One and the beginning of Act Two.

-

Act Two: The rising action element shows the protagonist facing various obstacles and challenges as they try to resolve the conflict.

- The *dilemma sets the stage for the character development and growth of the protagonist and their allies.

The rising action leads to the climax, which is the turning point or the most intense moment of the story. The climax marks the end of Act Two and the beginning of Act Three.

-

Act Three: This act corresponds to the falling action and resolution elements of Freytag’s Pyramid. It shows the consequences and outcomes of the climax, and how the protagonist deals with them. It also answers the dramatic question that was raised by the inciting incident, and wraps up any loose ends or subplots. The resolution is followed by the denouement, which is an optional element that provides a sense of closure or finality to the story.

NOTE: I leaned heavily on the Bing robot for language and structure in discussing the above. The language was likely lifted from these sources:

- Freytag’s Pyramid: Definition, Elements and Example

- Freytag’s Pyramid and the Three-Act Plot Structure

- The 5 Stages of Freytag’s Pyramid: Introduction to Dramatic Structure

Here is my sense for how this plotting, pyramid approach might be visualized.

Dramatic Milestones

Dramatic milestones are key events or turning points in a novel that advance the plot, develop the characters, and create tension and suspense for the reader. They are also known as plot points, story beats, or dramatic units. Dramatic milestones are essential for creating a satisfying and coherent story structure that keeps the reader engaged and invested in the outcome of the novel. Dramatic milestones are meant to serve your story and your reader by creating a clear, coherent, and compelling narrative arc that keeps them hooked from start to finish.

There are different ways to organize and identify dramatic milestones in a novel, depending on the genre, style, and purpose of the story. However, some common dramatic milestones that most novels share are:

-

The hook: This is the opening scene or chapter of the novel that introduces the main character, the setting, and the conflict. The hook should capture the reader’s attention and curiosity and make them want to read more.

-

The inciting incident: This is the event or situation that triggers the main character’s journey or quest. It disrupts their normal life and presents them with a problem, a challenge, or an opportunity that they must pursue or overcome.

-

The first plot point: This is the point where the main character makes a decision or takes an action that commits them to their goal and sets them on a new course. It marks the end of the first act and the beginning of the second act of the novel.

-

The midpoint: This is the middle point of the novel where the main character faces a major crisis, a reversal, or a revelation that changes their situation or perspective. It can be either a positive or a negative event, but it should raise the stakes and complicate the conflict.

-

The second plot point: This is the point where the main character receives new information, resources, or allies that help them prepare for the final confrontation or resolution. It marks the end of the second act and the beginning of the third act of the novel.

-

The climax: This is the highest point of tension and excitement in the novel where the main character faces their ultimate challenge or enemy and achieves their goal or fails to do so. It is also known as the turning point, as it determines the outcome of the story.

-

The resolution: This is the final scene or chapter of the novel that wraps up the loose ends, reveals the consequences of the climax, and shows how the main character has changed or grown as a result of their journey. It should provide a sense of closure and satisfaction for the reader.

Depending on your creative vision and artistic expression, you can modify, add, or omit some of these milestones to suit your story needs.

Character development

Character development is the process of creating fictional characters with the same depth and complexity as real-life human beings. It is an essential element of writing a novel, as it makes the readers care about the characters and their journey. Character development involves several steps, such as:

- Giving your characters a background, personality, motivation, and goal that explain who they are and what they want.

- Giving your characters strengths and weaknesses that make them realistic and relatable.

- Giving your characters external and internal conflicts that challenge them and create tension and suspense.

- Giving your characters a character arc that shows how they change or grow over the course of the story.

- Giving your characters distinctive features, mannerisms, and voices that make them stand out from each other.

To help you with character development, you can use various tools and techniques, such as:

- Creating a character profile or sketch that summarizes the main traits and details of your character.

- Using a character development template or worksheet that guides you through the process of building your character step by step.

- Researching your character’s background, culture, occupation, or interests to make them authentic and believable.

- Writing from your character’s point of view to get inside their head and understand their thoughts and feelings.

- Using dialogue to show your character’s personality, voice, and relationships with other characters.

- Showing, not telling, your character’s emotions, actions, and reactions through descriptive language and imagery.